WORKSHOP, WRITING, AND DESIGN

The next “phase” of the theater creation process can be loosely labeled the “workshop” or “rehearsal” period. Most of the writing and crafting of the piece will happen during this phase. Despite the structure of rehearsals, most of the writing and design will happen simultaneously. Due to economic constraints, it is likely that the ensemble will be working in intense developmental periods over a series of short-term residencies. This could range from a handful of days to a few weeks, and will differ on a case-by-case basis.

A note on time. As was discussed earlier with space and place, pay careful consideration to the duration of the workshop and set your goals accordingly. In addition, availability of ensemble members may vary from rehearsal period to rehearsal period, so pay special attention to base your goals on this availability. Perhaps the workshop is a period of intense experimentation after which the writer can spend the following few months developing a script. Perhaps this is a time to test the possibilities of technology and give the designers time to experiment, with actors. Perhaps it is a time to refine a certain section of the piece that just isn’t quite working out for one reason or another. Most importantly, this time is still a time of development, and goals should be set in place that reflects this.

I believe this period of time to be the most critical for the Producer in regards to forming a bond with the director and to really strive toward a true sense of ensemble. Working within the director’s preferred structure (and do keep a keen eye on the structure and schedule of rehearsals), the producer has an opportunity to engage all members equally, both to support the ensemble’s vision, but to also keep a finely tuned sense on the pacing of the development in regards to the larger artistic goals of the piece (as agreed upon in the first phase). Is the piece still on track? Are the artistic goals changing? If so, how much? Is the piece still in alignment with grant guidelines and programming commitments (if any)?

While the nature piece will certainly change with each workshop, it is imperative that the producer understands exactly how each element of the piece is progressing along the way.

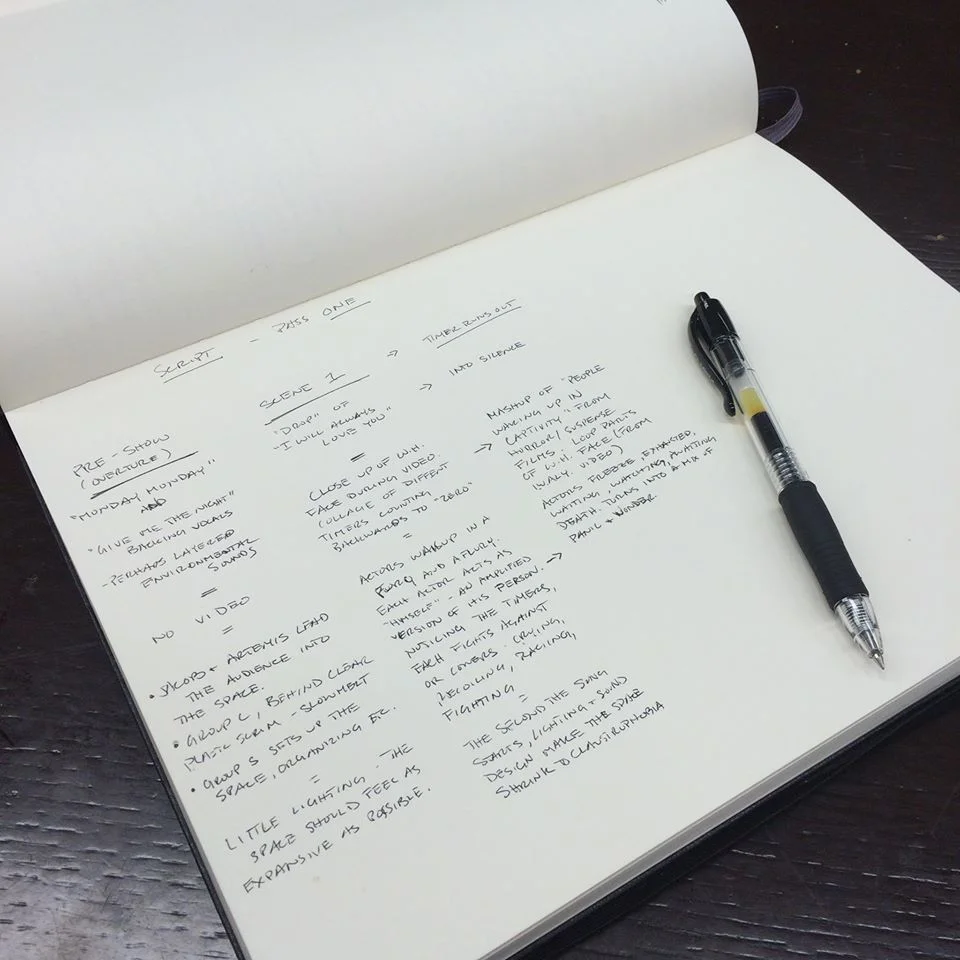

The structure of the written page can help immensely in this process. Douglas Kearny, poet and librettist, offered me a myriad of suggestions when developing a script that lends itself to an ensemble-based process, as opposed to a script that dictates a hierarchical development process. With the development of my own project, I found the script itself quite troubling. Essentially, I felt that a typical script wasn’t capturing the essence of what I had been developing in workshop, but was functioning more as a roadmap for other artist’s remounting. This would be fine if that was the intent of the piece, but I more so wanted the script to be a visual extension of the aesthetic of the work on stage. In essence, the script should be just as confusing, performative and overwhelming as the piece of theater.

Beginning script for #THESIS2015. I tend to write out my multimedia scripts like music scores.

The solution was to create a script full of indicators, but no clear destination; to evade a “top down” development structure (with the director and writer at the top). The goal became to develop a script that could not be interpreted solely by one person. Instead, it would take an entire ensemble to search out (and in some cases invent) the nuances of the script and explore all the different options for translating that onto the stage. This, however, is in an instance where the director is also the “writer”. Wither different people occupying those two roles, it would be a good idea to think about the form, function, and structure of the script from the onset, as it’s being developed.

Despite the form of the script, many facets of the design phase will also occur during this workshop stage. This can be tricky, as each designer will most likely bring their own processes into the rehearsal space, and will have different ways of interfacing with the project as it progresses. Also, take special note of how important each design element is in the piece. If video design is an integral part of the ensemble’s product, you may want to make a goal of having the designer present at as many rehearsals as possible. If the ensemble prefers a more traditional approach to lighting, the lighting designer may only be needed in the final workshops, once the stage business is solidified. Take this time to be honest about which designers could benefit from each workshop phase, and how the ensemble might benefit from dialogue with designers.

When making these considerations it is also critical to balance the technical needs and desires of the director an designers with the technical capabilities of the space in question. Ideally, designers will be added into the process as more specific technical needs can be addressed, and this planning should begin as soon as possible, in an effort to make the best use of everyone’s time.

Another note on time: It is wise to allot for appropriate amounts of time technical rehearsals and unfolding design processes throughout the development of the work. Inevitably changes will be made as “scripts” are derived and workshop spaces change. Prepare carefully for the designers needs, so not to lose precious time while in a space.

“Super Vision’s process of collective creation means that the time-consuming changes must be made on the march. At one point during rehearsals at St. Anne’s video designer Peter Flaherty asks to change the timing of a video transition. ‘Just a second,’ he calls.

“’Someone’s gonna start a lexicon of Builder’s terms,’ says Marianne Weems dryly. ‘”One Second” mean at least two minutes.’ She might be talking for anyone working with video in theater…Time is always of the essence. In most ball games, the ball is in play for much less than game time. So in devising. We forget this at our peril.”

- Harvie, Lavender – “Making Contemporary Theater

“A technical element needs as much detailed examination as any other eleent of the show. It is common practice to work in a really detailed manner to improveise back-stories or learn a historically accurate period dance – yet pay no attention to the dramaturgy of a technical elements.

“When you have the equipment on the room you can ask, “Why is this man flying? What is his relation to the people on the ground? How do you incorporate video into the flying work? These become puzzles to be solved by the company. They can only be posed and then answered through exploration – through endless devising tasks, most of which seem to turn up barren earth. Then a gem appears and the meaning of the process becomes clear” – Catherine Alexander

- Harvie, Lavender – “Making Contemporary Performance”

- Take special note at the beginning of the process to the interests and background of each designer on board. Is this the designer’s first time working with the ensemble? How is the designer fulfilling personal and artistic goals by developing the work?

- Are the designers on track in supporting the artistic goals of the production?

The answers to these questions may give insight into levels of investment and how to best approach each designer throughout the workshop process. Also, be aware of idiosyncratic vocabularies of frequent collaborators, and learn to assess how these language patterns effect development (both aesthetically and in regards to time).